Nature has always been a random architect. Entering Petralona Cave, which was formed in the limestone of Katsika Hill about a million years ago, makes this very clear.

The cavern, known as “the cave of the red rock” because of the color that the bauxite deposits give to the stone, has an area of 10,400 m2 and is full of stalactites, stalagmites, curtains and shields, columns and other formations. Its discovery in 1959 opened a window to the prehistoric period.

It is currently the most important of Greece’s 12,000 caves due to its abundance of fossils (one of the richest collections in Europe) and the discovery of the oldest human remains ever unearthed in Greece about 50 years ago.

The strange hole at the base of Katsika Hill was initially discovered by residents of the Petralona settlement. They made a small entrance, climbed down on a rope and then re-emerged carrying teeth and bones of petrified animals which they presented to Professor Petros Kokkoros of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Greek scientists began excavating the site, revealing passages and gathering artifacts after the discovery inspired the scientific community. The cave quickly became known outside of Greece as a treasure mine of geological and anthropological artifacts.

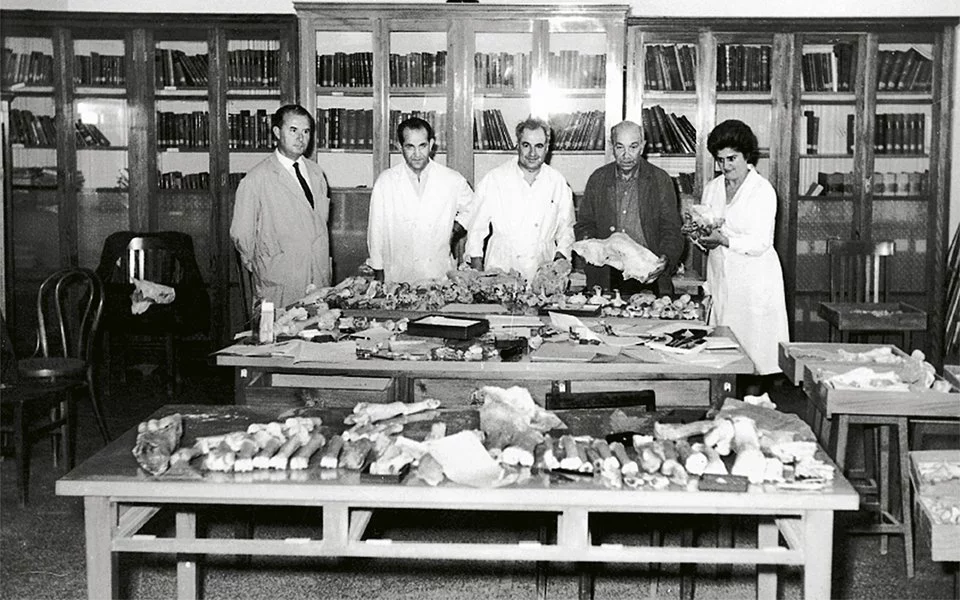

Scientists made their most important find in September 1960 when they discovered a fossilized human skull among hundreds of other animal fossils from 22 different species, including extinct bears, lions and hyenas.

The physical characteristics of the skull suggest that it belonged to a person who evolved from Homo erectus to Homo sapiens. After much research and discussion, it is now believed to be 200,000 years old.

An essential component of the human evolutionary puzzle was the skull. The “Parthenon of paleontology” has been researched by some of the world’s best paleoanthropologists.

Although the cave has not yet been fully explored, an artificial tunnel provides convenient access for tourists to appreciate the intricate formations and two examples of rock art.

One shows a bear, which is near the original entrance to the cave, and the other shows people eating.

However, it has not yet been established whether people originally resided in the cave. There could have been an accident with the skull.

Paleontologist Dr. Evangelia Tsoukala, a professor at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and one of the researchers who examined the items recovered from the cave, says that future research involving international collaboration and new techniques will tell us exactly what happened.

She says: “Halkidiki continually produces fossils.” “In Kryopigi we found a giraffe, a wild boar, small mammals, large and small carnivores and three different species of prehistoric horses.

The most important fossil we discovered was one of the best-preserved skulls of an Old World monkey called Mesopithecus pentelicus.

Researchers discovered a set of teeth from the upper jaw of a Deinotherium, a trunked, tusked animal that roamed the world between 5 and 10 million years ago, at another location called Aghia Paraskevi.

They found numerous fossilized tree trunks in Kassandra and evidence of huge turtles on the coast of Halkidiki.

Next to the cave there is an Anthropological Museum, a 1,000 m2 structure with 400 display cases and more than 2,500 finds not only from Halkidiki but also from other sites investigated by the Anthropological Association of Greece.

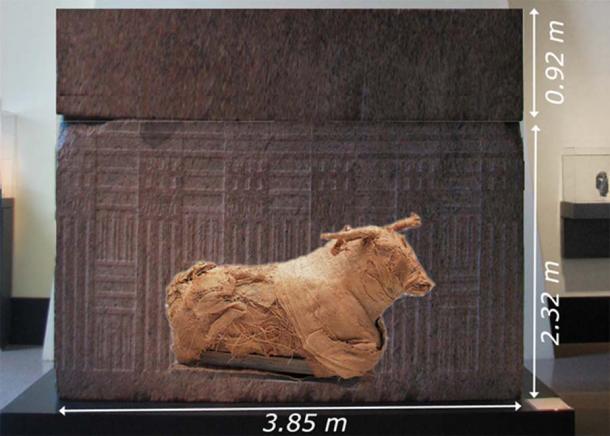

On display are fossils of large mammals discovered in the Petralona cave, stone and bone tools and fossils from various places in northern Greece.

The well-known human skull is on display at the Aristotle University Museum of Geology and Paleontology, along with a considerable number of casts and other global finds.